Successfully performing a magical illusion demands a wide range of knowledge and skill. This includes an understanding of certain scientific principles and embracing the advances technology brings: magic, like science, is always changing but similarly many of its fundamental principles stay the same.

Gustave Kuhn launched his new book Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic here at Senate House Library on 14 March. It explores how the scientific study of magic can give insights into the working of the human mind. I will look at how magic itself has often had a fruitful relationship with science, as explored in the ‘Magic and Innovation’ section of the Staging Magic –The Story Behind The Illusion exhibition.

Philosophical Amusements

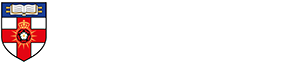

Against the background of the enlightenment, conjurors exploited the popular interest in science to attract audiences to their performances. ‘Philosophical amusements’ were advertised with promises of mechanical and philosophical marvels as well feats of sleight of hand and ingenious deceptions. Increasingly, these performers were based in halls, theatres and assembly rooms, similar to the venues used for public science lectures. ‘Professor of Natural Magic’ Chevalier Giuseppe Pinetti was one of the most successful of these scientific conjurors in the late 18th century, selling out shows across Europe and arriving in London to perform at the Theatre-Royal Haymarket in 1784. Notices for his performances entice the crowds with promises of ‘the most wonderful stupendous and absolutely inimitable mechanical, physical and philosophical pieces which his recent deep scrutiny in those sciences, and assiduous exertions have enabled him to construct and invent.’ The notice for Pinetti’s performance of 2nd December 1784 includes a ‘Signora Pinetti’ on the bill. She acted as the medium in a second sight act where she would ‘guess at everything imagined and proposed to her’ while blindfolded. This trick was most likely achieved through code words, a technique that would be developed and refined by performers over the following century.

In the same year as his London season, Pinetti published a book: Physical Amusements and Diverting Experiments, intended not to reveal his secrets but to provide some small amusement to its reader. It included both scientific experiments and more traditional conjuring tricks. The engraved frontispiece of the book features a bust of the man himself, being crowned with laurels by putti and surrounded by scientific paraphernalia, including a cat in a bell jar. The book was a response to an exposure of Pinetti published in 1785 by lawyer, mathematician and amateur conjuror Henri Decremps. La Magie Blanche Dévoilée and its supplement revealed the secrets of Pinetti’s tricks and illusions. An English translation was published in 1788 as The Conjurer Unmasked and a new style of revelatory conjuring book was established, combining explanations of scientific demonstrations and legerdemain.

Scientific Recreations

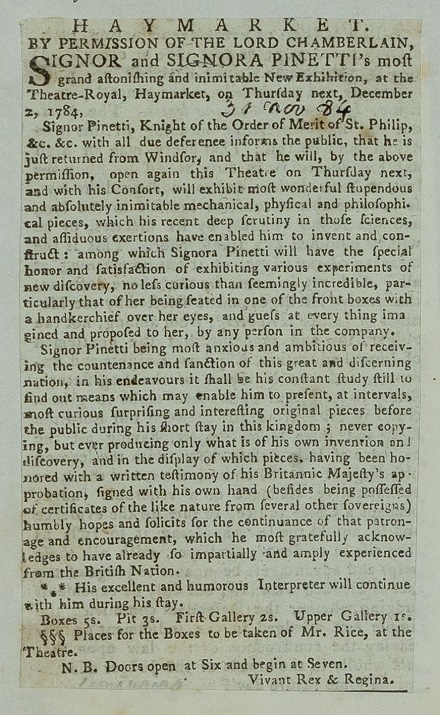

Throughout the 19th century, sleights and card tricks were frequently published alongside scientific recreations, particularly in books aimed at children. This was in part an extension of enlightenment ideas on education and rationality: tricks that would otherwise appear impossible to the unenlightened were given a firm scientific basis. Books such as Parlour Magic (1838) described the boundaries legerdemain as ‘extended by the assistance of chemistry and a knowledge of the principles natural philosophy’. Staging Magic features a typical book from the late 19th century, Scientific Mysteries (1891), which describes experiments with gases, phosphorus, metals, crystallisation and, perhaps for topicality, ‘nihilist bombs’. But it also includes popular stage illusions of the time, with a version of the Sphinx illusion illustrated under the title ‘Decapitation no murder.’

Education, science and magic

![A lady vanishes, from Will Goldston's Stage Illusions ([1912])](../assets/images/blog/HPL_Goldston_0002_0.jpg)

John Henry Pepper was one figure whose work bridged education, science and magic remained closely linked throughout the 19th century. His name is best remembered for Pepper’s Ghost, a stage illusion adapted from an original idea of Henry Dircks, the ‘Dircksian Phantasmagoria’ in which a ghostly projected image appeared on a stage. Pepper made the effect workable in existing theatres, and his name became associated with it. He was also a prolific author of books of popular science aimed at children and lectured in schools. The Boy's Playbook of Science first published in 1860, encouraged its reader to cultivate useful knowledge in the sciences alongside other leisure pursuits. The book, and its revised edition, covered the principles behind many of the technological marvels of the age as well as many of the elements of optics, angles and sightlines that are essential to successful stage illusions.

Illusion and Innovation

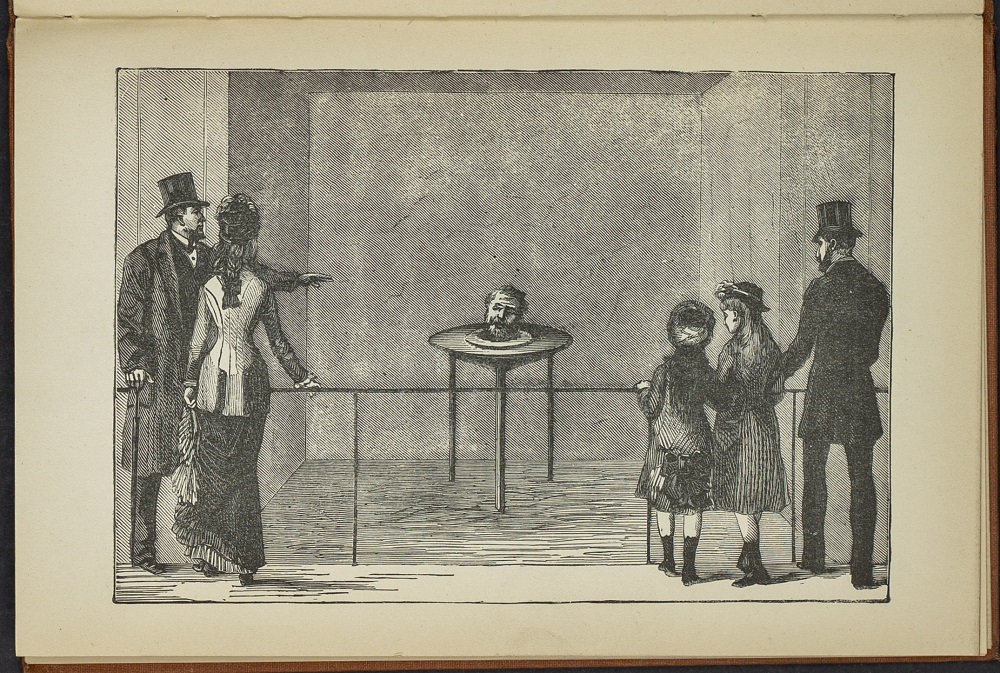

As 18th century conjurors embraced new and popular scientific ideas in their performances, their successors a century later also used new techniques and advances in technology to stage ever more dazzling illusions. From the mid-19th to early 20th century, many new illusions were created, establishing principles that are still used by stage illusionists today. These included levitations and aerial suspension, vanishing acts, new versions of illusory decapitations and, in the 1920s, the sawing-a-woman-in-half trick.

The British magician David Devant was a leading illusionist

of this golden age of magic and in 1935, long after his retirement from performing, he published an article in the Windsor Magazine titled ‘Illusion and Disillusion’. Here, he explained the secrets behind some of his

most famous acts in the hope that by this disillusionment, the student of magic would ‘be goaded into doing something more wonderful himself. There are greater facilities to-day, with the advance of scientific appliances’.

Unfortunately, by publishing his secrets in a popular magazine, Devant fell foul of the Magic Circle’s rules on exposure and he was excluded from the organisation. By exposing his own secrets, Devant destroyed their

mystery and romance, but his intention, through his own form of enlightenment, was to inspire innovation and advance the art of magic.

The British magician David Devant was a leading illusionist

of this golden age of magic and in 1935, long after his retirement from performing, he published an article in the Windsor Magazine titled ‘Illusion and Disillusion’. Here, he explained the secrets behind some of his

most famous acts in the hope that by this disillusionment, the student of magic would ‘be goaded into doing something more wonderful himself. There are greater facilities to-day, with the advance of scientific appliances’.

Unfortunately, by publishing his secrets in a popular magazine, Devant fell foul of the Magic Circle’s rules on exposure and he was excluded from the organisation. By exposing his own secrets, Devant destroyed their

mystery and romance, but his intention, through his own form of enlightenment, was to inspire innovation and advance the art of magic.

Magic and science have long gone hand-in-hand, enabling magicians to give their audiences an experience of the impossible. But there is much a scientific approach can reveal about psychology of magic in performance and in our everyday lives.