“The hopes of the world rest on young people. Peace, economic dynamism, social justice, tolerance — all this and more, today and tomorrow, depends on tapping into the power of youth”, António Guterres, UN Secretary-General

The universalism of these words to mark International Youth Day on 12 August, resonates with much of the work that Clara Ellen Grant (1867-1949), a London pioneer of infant children’s education, undertook in the East End in the early decades of the twentieth century.

The universalism of these words to mark International Youth Day on 12 August, resonates with much of the work that Clara Ellen Grant (1867-1949), a London pioneer of infant children’s education, undertook in the East End in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Beginnings

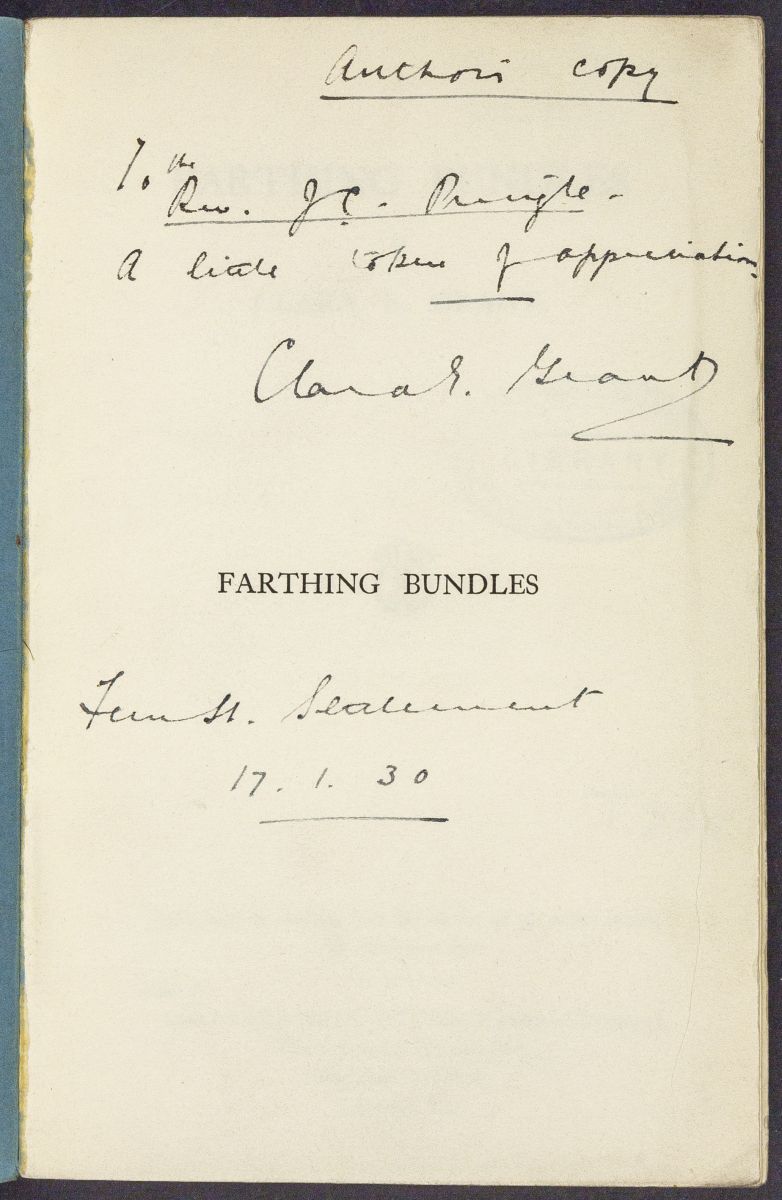

Her story is featured in the Rights for Women: London’s Pioneers in their Own Words exhibition, through the lens of the two autobiographical accounts that she self-published to raise funds for her educational and philanthropic work. These two books: From ‘Me’ to ‘We’: Forty Years on Bow Common (1930) and Farthing Bundles (1930) chart a life well lived and fully devoted to the causes of social work with the poorest families in London, and particularly their children. Both works are held in the library of the Family Welfare Association, one of Senate House Library’s most significant and distinctive special collections relating to social work history, which has been recently gifted by Family Action, the successor organisation.

Born into a relatively prosperous and educated Wiltshire family in 1867, Clara’s greatest ambition as a young woman was to further her education and become a teacher in London. She completed her training at Salisbury Diocesan Training College in 1886.

She fulfilled the first part of her dream of becoming a teacher in a church school at a small Wiltshire village in 1888. Only two years later she managed to fulfil the second part of that dream when she took up the post of head at a school in Hoxton, London. Except for a short and unhappy spell teaching at a boarding school, Clara was determined to work with the poorest and the most deprived in London.

East End Calling

Clara put theory to practice as soon as she set foot in the little tin school at Bow Common, where she was appointed head teacher in 1900. The district was undoubtedly one of the most dangerous in the city, as evidenced by Charles Booth’s pioneering work Labour and Life of the People in London (1892-1897). However, where others saw danger and depravation, Clara saw people who endured abject destitution and hardship, but who deserved respect and dignity. To that end she set out to improve their lives, and particularly those of young children, through education.

“These pictures will convince my readers that something had to be done to help the children socially if school education were not to be both cruel and ineffective”, Clara E. Grant, Farthing Bundles, London: Grant, 1930.

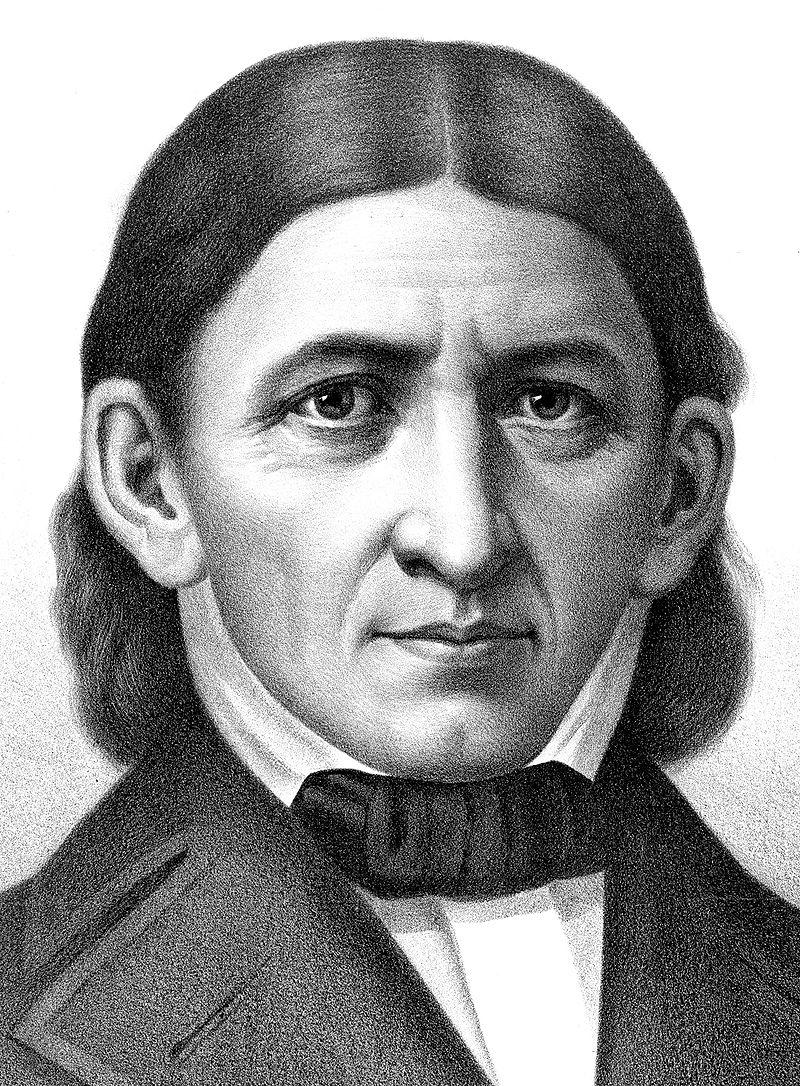

Her outlook was greatly influenced by the social and educational reformist ideas

of her time. She was a staunch follower of Froebel’s method of education. This school of educational thought founded by Friedrich Froebel, a German educator who invented the kindergarten, considered the whole child’s,

health, physical development, the environment, emotional well-being, mental ability, social relationships and spiritual aspects of development equally important.

Her outlook was greatly influenced by the social and educational reformist ideas

of her time. She was a staunch follower of Froebel’s method of education. This school of educational thought founded by Friedrich Froebel, a German educator who invented the kindergarten, considered the whole child’s,

health, physical development, the environment, emotional well-being, mental ability, social relationships and spiritual aspects of development equally important.

Another significant influence in her thinking was the Settlement movement, which was active in England and the United States from the 1880s to the 1920s. Its primary aim was to bring the poor and the wealthier in closer vicinity within low-income districts, in the hope that the middle-class settlement ‘workers’ would share knowledge and culture with their neighbours. The first such settlement in England was Toynbee Hall, founded in 1884 under the auspices of Canon Samuel Barnett.

Clara’s own Christian convictions and Liberal Party sympathies also played a part in embracing this movement.

A firm believer that individuals should be empowered to take responsibility for their own lives, she was also motivated by compassion and charity towards those who lacked everything.

Clara’s own Christian convictions and Liberal Party sympathies also played a part in embracing this movement.

A firm believer that individuals should be empowered to take responsibility for their own lives, she was also motivated by compassion and charity towards those who lacked everything.

The 'Farthing Bundles'

Clara’s experience of working at Toynbee Hall for a short period deeply influenced her future social work as she established the Fern Street settlement in her own house at Bow Common. This modest enterprise rapidly evolved into a well organised structure within the neighbourhood, where families could turn for help in case of emergency.

Undoubtedly one of the most pioneering aspects of the Fern Street settlement was the children’s school, and what it provided for the youngest and most vulnerable members of the community. As well as introducing school breakfasts and having the first school nurse in London, the school allowed sleep time for the smallest children. In terms of her educational work Clara implemented modern teaching methods in early childhood education, and particularly a new classroom structure which promoted the health and welfare of children as a means to create the conditions for a better and more just society. As a firm advocate for the pedagogical views of the Child Study Movement, she was at the forefront of educational reform.

Furthermore, she considered play and recreation central to a child’s development. Seeing the lack of the most basic things among the young children of the East End, she began to make up bundles of small odds and ends, toys, trinkets, pencils and sweets that she sold to them for a farthing, the smallest currency available at the time, and in Clara’s own words:

“A most important coin of the realm on Bow Common. A child with a ¼ d. of sweets was relatively rich, but when there were two or three children and one farthing, the obliging shopman would pack the sweets into two or three little packets and so made more little people happy, and also relieved them of the responsibility of sharing them round”,

Clara E. Grant, Farthing Bundles, London: Grant, 1930

“A most important coin of the realm on Bow Common. A child with a ¼ d. of sweets was relatively rich, but when there were two or three children and one farthing, the obliging shopman would pack the sweets into two or three little packets and so made more little people happy, and also relieved them of the responsibility of sharing them round”,

Clara E. Grant, Farthing Bundles, London: Grant, 1930

The symbolic value placed on the small parcels gave the children a sense of dignity for being able to afford them and also encouraged them to share and play. As one of the parents shrewdly pointed out to Clara ‘the toys and other useful articles keep the minds occupied’.

Although Clara Grant died in 1949, her legacy continues to be present in the area where she lived and worked most of her life. The Clara Grant Primary School in Tower Hamlets and the Fern Street Settlement are testament to her pioneering educational work, and its transformative influence on the community she served so well.

Dr. Maria Castrillo

Head of Special Collections & Engagement & Co-Curator of Rights for Women: London's Pioneers in their Own Words

Further Reading:

‘A School Settlement, 1911’ in Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920, Ellen Ross (ed.), University of California Press, 2007, pp. 81-88

D. Copelman, London’s Women Teachers: Gender, Class and Feminism, 1870-1930, Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, 1996

Clara E. Grant, Farthing Bundles, London: Grant, 1930

Clara E. Grant, From ‘Me’ to ‘We’: Forty Years on Bow Common, London: Grant, 1930