I’d like to ask you to try a little exercise of imagination…

It is 1877. We are sitting in an open court. On trial

is a 29-year old woman. She is charged with having published an ‘obscene libel’ – a re-print of Fruits of Philosophy,

a book about contraceptive methods, first published some 40 years earlier. She defends herself in front of an all-male jury. The young woman stands proudly, her personality is magnetic; she is passionate and delivers

a lengthy address. She is a free thinker, her speech is eloquent, and her language is glowing.

It is 1877. We are sitting in an open court. On trial

is a 29-year old woman. She is charged with having published an ‘obscene libel’ – a re-print of Fruits of Philosophy,

a book about contraceptive methods, first published some 40 years earlier. She defends herself in front of an all-male jury. The young woman stands proudly, her personality is magnetic; she is passionate and delivers

a lengthy address. She is a free thinker, her speech is eloquent, and her language is glowing.

“I put it to you that there is nothing wrong in a natural desire rightly and properly gratified. There is no harm in feeling thirsty because people get drunk; there is no harm in feeling hungry because people over-eat themselves, and there is no harm in gratifying the sexual instinct if it can be gratified without injury to anyone else, and without harm to the morals of society and with due regard to the health of those whom nature has given us the power of summoning into the world.[…] if you are to blame Dr Knowlton because he recognises a great natural fact, then it is your duty to blame the constitution of the world,”*

This woman and her partner in crime, Charles Bradlaugh, defend themselves for five days in this court. The solicitor general, unconvinced by the witnesses, declares the publication “a dirty, filthy book” that no one would willingly allow to lie on his table and no English husband would allow even his wife to have it. The jury, after discussing the case, is unanimous in the opinion that the book will deprave public morals, but “entirely exonerates the defendants from any corrupt motives in publishing it.”

The defendants are sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, fined 200 pounds, and forbidden to publish the book for a period of at least two years. They ignored the warning and continued to publish.

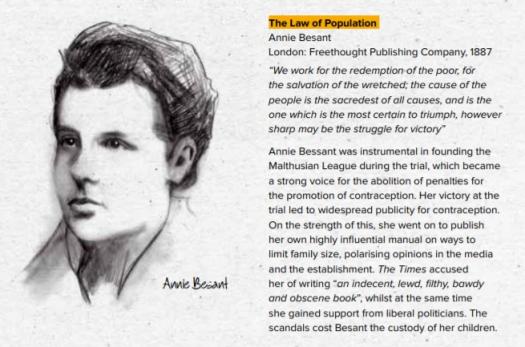

The overall effect of the trial was huge publicity for contraception and family planning for years to come. This was one of the most celebrated trials of the 19th century and the woman was Annie Besant.

The defendants are sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, fined 200 pounds, and forbidden to publish the book for a period of at least two years. They ignored the warning and continued to publish.

The overall effect of the trial was huge publicity for contraception and family planning for years to come. This was one of the most celebrated trials of the 19th century and the woman was Annie Besant.

Continuing Her Story…

For the last few months while co-curating Rights for Women: London’s Pioneers in their Own Words, I have been immersed in the personal stories of so many extraordinary women like Annie Besant. Trailblazers each in her own way. Each making a statement fighting for a cause, supporting other women, or forging a career.

Annie Bessant was described as “the only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion” by Beatrice Webb, who is another pioneer featured in Senate House Library’s Rights for Women: London’s Pioneers in their Own Words exhibition; she co-founded the London School of Economics and The New Statesman with her partner Sidney Webb.

The items in the exhibition display the inspiring stories of women breaking barriers as told through their own words; giving them a platform, reviving their voices and showing the personal sacrifices they made. The strength of all the women in the exhibition is strikingly alive and so is the powerful story of their collective voice, of the associations they formed, and the organisations they founded and led. We hope you will be inspired to share the achievements of these women and join us in ‘Continuing Her Story’.

Mura Ghosh

Research Librarian & Co-Curator of Rights for Women: London’s Pioneers in their Own Words