“In a lonely Berkshire coppice he set up a hidden hut…He was making … books with his own hands. Not ordinary books.” Reid, 1970, p.141

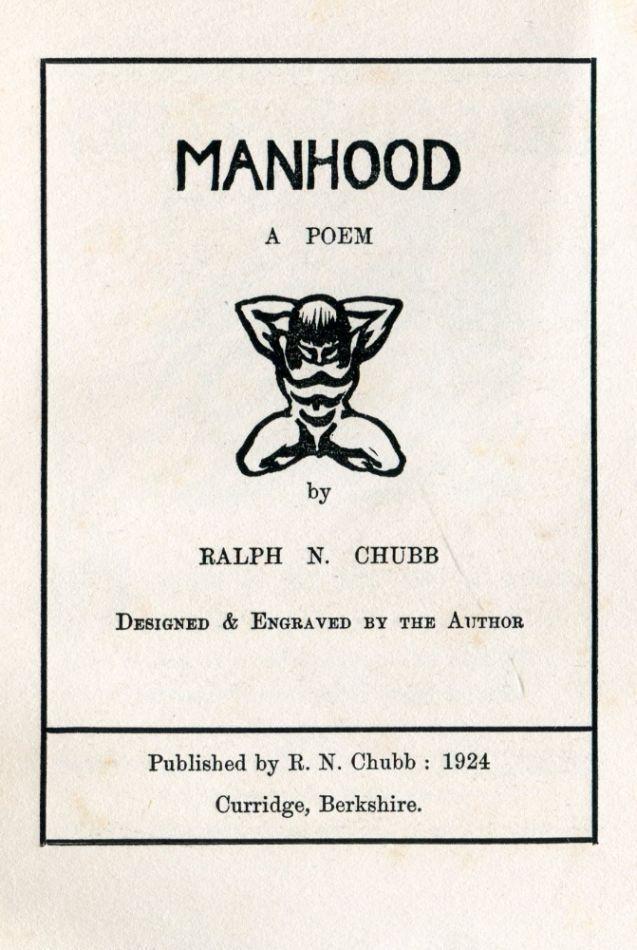

One of the works on display in the Queer between the Covers exhibition is a four page printed pamphlet entitled Manhood. This pamphlet, with its grey and black cover striking in its simplicity, was published in 1924 by the British poet, printer and artist Ralph Chubb

(1892-1960). Ralph Chubb, if acknowledged at all, is often mentioned as an aside: to the British private press movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the ‘Uranian’ literary coterie

of the same period.

One of the works on display in the Queer between the Covers exhibition is a four page printed pamphlet entitled Manhood. This pamphlet, with its grey and black cover striking in its simplicity, was published in 1924 by the British poet, printer and artist Ralph Chubb

(1892-1960). Ralph Chubb, if acknowledged at all, is often mentioned as an aside: to the British private press movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the ‘Uranian’ literary coterie

of the same period.

The word “eccentric” features regularly in the pieces that have been written about him. Despite this, Chubb’s early artistic life began conventionally enough with time spent studying at the Slade School of Fine Art and works exhibited in major London galleries, often with the support of Leon Underwood (Reid, p.152). However, by the end of his life he was reduced to sending gratis unsold copies of his works to libraries and galleries in the hopes that by doing so his art would survive him.

Torment or Talent?

Regard for his talent varies enormously. In 1970 Timothy D’Arch Smith described Chubb as having produced interesting printed works but as lacking in poetic ability; he views these facets as intertwined, particularly as Chubb’s work developed over time, and that “as practical ability increases so does the pathological breakup of thought, expression, and intent” (p.220). The same year, however, Anthony Reid described the “wonderful drawings that crowd the pages” (p. 156) and endeavoured to revive Chubb’s reputation.

Ralph Chubb was, by his own admission, hugely influenced by the work of William Blake, by his combination of words and images uniting in a holistic artistic process to express a prophetic personal vision. As Roderick Cave describes, he was a “complete artist” (p.59) and Chubb believed himself to be an artistic descendent of Blake’s (Cave, p.60). His vivid imagination was apparent from childhood, when he believed himself to have been “a monk-illuminator” in a former life (Reid, p.143).

Pressing issues:

Manhood was the first work Chubb published, and it was undertaken with the assistance of his brother Laurence. Laurence had created for Ralph a basic printing press using a carpenter’s bench as the basis; whilst Ralph wrote the words and designed and engraved the blocks, the pamphlet states at the end that it was “printed by L.J. Chubb with the hand-press made by him”. The familial hand was also present in the typesetting, a process Ralph disliked, and which was undertaken by his sister Ethel (Reid, p.152). For his later works, Chubb rejected type in preference for script; producing his books entirely by hand, each could take years to produce (Reid, p. 154).

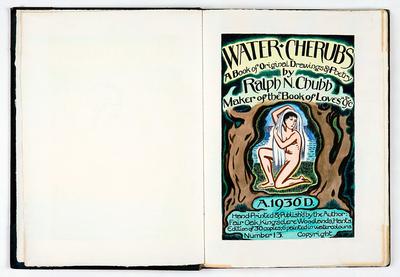

Chubb’s works tend to be referenced as undergoing distinct design phases. He produced three books on the primitive home printing press which were followed by a spate of text submission to commercial printers, before he turned once more to self-publishing, this time using lithography. Due to his increasingly labour-intensive, hand-written and illustrated method of book production, many of his works were produced in very small editions. Whereas the typeset Manhood was printed in an edition of 200, Chubb’s lithographic works were produced in minimal quantities: the Water Cherubs (1936), for example, was published in an edition of 30.

The politics of the personal:

The content of Chubb’s work also underwent various manifestations. Chubb’s sexuality was apparent throughout his work: Manhood, a paean to the male body, exemplifies this. It certainly seems that part of the reason Chubb’s works are often considered as merely an afterword to those of his contemporaries is that he was a gay man, openly expressing his sexuality, at a time when this was deemed unacceptable. Although his works were held at the British Museum they were kept in the “private case”, the repository of works considered obscene or sexually explicit, access to which was restricted and required application to the librarian to determine the intention of, and effect of the works upon, the reader.

It is also the case, however, that over time as Chubb’s works developed artistically they also increasingly depicted troubling subject matter; as D’Arch Smith notes, his works became distinctly paedophilic in nature, both in the text and illustrations of nude boys, albeit often shrouded in a mystical, occult terminology (p. 220). As such, Chubb often failed to sell even the limited copies of his works and Reid reports that some were destroyed, denounced or burnt (p.141).

The visibility of Chubb’s work today:

.jpg)

Considering Chubb today, his work has not entirely disappeared from view. His archive and copies of his books are held in the Ralph Chubb Memorial Collection in the Meermanno Museum in The Hague. The Museum has elected to highlight the aforementioned Water Cherubs on their website. His works are also often sold via the Elysium Press who were founded to print and sell books that have fallen from fashion.

Whilst it is a stretch to view Chubb’s visionary art as equivalent to Blake’s, there is something charming and indeed beautiful about his printing style as evidenced by the simplicity of the early block design and his later handwritten script accompanying his colourful illustrations. His impulse to print and create an all-encompassing vision of combined poetry and text is an appealing one, and quite different from the arts and crafts influenced private presses he developed alongside; his work provides an interesting aesthetic impulse and counterpoint to them. Manhood is a perfect example of Chubb’s interesting, quirky and striking early printing style.

However, due to their nature, not all his works are as easy to read with pleasure, and attempting to view them solely as printed art, whilst ignoring the subject matter, is not only problematic but runs counter to their intended meaning. For Ralph Chubb the visual and the written were necessarily entwined and it is this that makes some of his works difficult to enjoy and I think why he is, and probably will remain, a curious and ultimately troubling footnote to the history of English private press printing.

Discover more about the world of queer publishing with us at our Queer Publishing / Publishing Queer conference on 16 March

Leila Kassir

Research Librarian: British, USA & Commonwealth Literature at Senate House Library

Leila Kassir

Leila Kassir