In art and literature of the last 130 years, few works have proven as controversial, as enduring, or as intrinsically queer as Oscar Wilde’s one-act play Salomé. Dr Will Visconti examines quite why there are such strong links between the figure of Salomé and queer or camp art, subculture and performance.

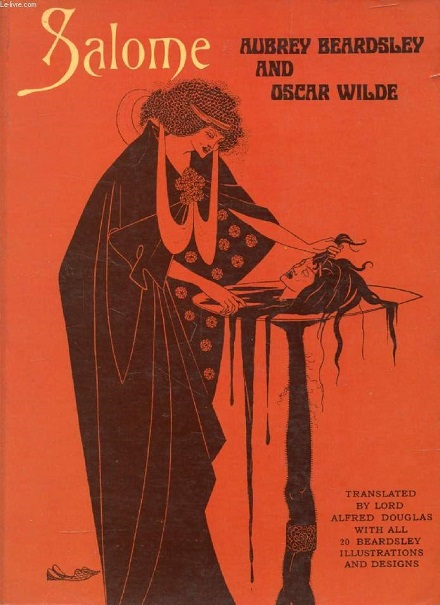

First penned in 1891 in French by Oscar Wilde, Salomé is a one-act play that has entered the canon of Decadent literature, as well as that of Decadent art, accompanied by the dark, sexually-charged illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley and translated into English by Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. However, the play is suffused with transgressive sexuality from every angle. The writer, artist, content and the proposed cast of the play are all queer, in one sense of the word or another. One can see how the exaggerated, stylised language and art of the piece, as well as their esotericism, fit so neatly within Susan Sontag’s “Canon of Camp”.

Both Wilde and Beardsley were key figures identified with a queer sensibility in art and literature that has persisted to the present, because of the nature of their respective oeuvres as well as their personal lives. Oscar Wilde was famously arrested for “gross indecency” in 1895, and Beardsley’s reputation was tarnished by association. In some quarters his friendship with Wilde was seen as closer than was entirely appropriate. It should be noted, however, that despite the associations of Beardsley and his work with queer figures or subtext, there is no definitive proof that he was anything other than asexual (posthumous rumours of incest with his sister notwithstanding). The inclusion of Beardsley’s illustrations to accompany the text of Salomé added a layer of frisson to Wilde’s work, after the former’s work with The Yellow Book, followed by his work with Leonard Smithers. Smithers was another friend and colleague of Wilde’s who dealt in erotic and pornographic literature, and who published the queer pornographic novel Teleny. The novel was composed anonymously but is sometimes attributed to Wilde, who was certainly involved, though to what extent is unclear.

When Salomé was composed, Sarah Bernhardt was keen to both produce and star in the play, though despite rehearsing the role, she did not follow through with her appearance when it was mounted in France. Bernhardt, the daughter of a courtesan, was also famously transgressive, and known for her independence and tireless self-promotion as much as for her electric stage presence. She also performed numerous travesti roles onstage, including Hamlet. The “Divine” Sarah Bernhardt was also followed in the press for her relationships (intimate or platonic) with men ranging from Edward VII to Gabriele D’Annunzio. At the time that she was announced as the star of Salomé, she was in her forties, and had recently starred as the nineteen year old Jeanne d’Arc, followed by an engagement playing Cleopatra – fusing the images of the exotic Other, the femme fatale and the younger woman in her casting as Salomé.

The play contains several layers of transgressive sexuality, interweaving the relationships between the characters. Salomé becomes as infatuated with Iokanaan the prophet as Narraboth the Syrian is enamoured of her, and he kills himself for love of her. It is implied that the Syrian, in turn, is the object of unrequited desire: that of Herodias’s Page. Salomé’s feelings for Iokanaan culminate in her kissing of his severed head, and she engineers Iokanaan’s execution by playing on her stepfather Herod’s lust for her. Moreover, her mother Herodias’ marriage to Herod (who slew his brother, Herodias’ first husband and Salomé’s father) is decried by Iokanaan as incestuous.

All the world's a stage...

Although the play was banned in Britain, the justification for the ban was not given as the narrative but the fact that there existed a law prohibiting the representation of Biblical figures onstage. Salomé was, however, performed in France for the first time in 1896. In 1905 Salomé was written as an opera by Strauss, and has since provided fodder for numerous other performers, such as Maud Allan. Allan’s performance of Salomé adds to the transgressive reputation of the piece, since she was dogged by accusations of lesbianism and association with sexual and legal deviance because of her brother’s criminal past. With the advent of film, stars including Alla Nazimova and Rita Hayworth appeared in the titular role. More recent retellings of Salomé include a flamenco version starring Aida Gomez directed by Carlos Saura in 2002, and in 2011 a documentary-cum-film entitled Wilde Salomé. This version was conceived of by Al Pacino, who stars as Herod alongside Jessica Chastain as Salomé, and was itself a reiteration of Pacino’s performances of Salomé onstage in 2003 and 2006 (with Marisa Tomei and Jessica Chastain respectively). In 2017 Matthew Tennyson played Salomé in an RSC production to mark the 50th anniversary of the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain.

That Salomé continues to inspire adaptations and performances speaks to the public’s enduring fascination with the world created by Oscar Wilde (with the help of Beardsley and Bernhardt), and Salomé’s power to challenge audiences, calling into question established ideas about identity and desire.

The 1893 edition on display as part of the Queer Between The Covers exhibiton at Senate House Library, is signed by Oscar Wilde in dedication to Aubrey Beardsley - to the only other artist who "knows the dance of the seven veils and can see that invisible dance".

Dr Will Visconti

Dr Will Visconti is a Visiting Fellow with the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory within the Institute of Modern Language Research at SAS

He is also a lecturer in the Cultural Studies Department at Central Saint Martins (University of the Arts, London). He completed his PhD in French Studies & Italian Studies at the University of Sydney. His primary areas of research include explorations of sexuality, transgression and representation, particularly during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Current projects include research into the life and legacy of women like the performer La Goulue, the Marchesa Luisa Casati, and the artists Rosaleen Norton and Vali Myers.

Dr Will Visconti

Dr Will Visconti